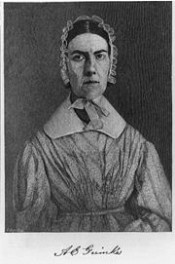

Grimke Angelina Emily

Angelina Emily Grimké Weld (20 February 1805 – 26 October 1879) was an American politician, lawyer, abolitionist and suffragist. Grimké was born in Charleston, South Carolina, to John Faucheraud Grimké, an aristocratic Episcopalian judge, planter, lawyer, politician, slaveholder, Revolutionary War veteran and distinguished member of Charleston society. Judge Grimké studied law in England and later enlisted in the Revolutionary Army as a Captain. At age 26 he was appointed Deputy-Adjunct General for South Carolina and Georgia under General Robert Howe. He was briefly imprisoned at Charleston, but was later paroled at which time he rejoined the Revolutionary Army. Judge Grimké fought in several famous battles, such as Eutaw Springs and Yorktown, before returning home as a Lieutenant-Colonel. After the war he served in South Carolina’s House of Representatives, one year of which he was named Speaker of the House. He was also a delegate to the South Carolina state convention for the ratification of the Constitution. He became a Judge in 1779 and also served as the Intendant-Mayor of Charleston. In 1784 he married Mary Smith, a descendant of Landgrave Thomas Smith, another family from the Charleston elite. Together they had a total of thirteen children, of which Angelina Grimké was the youngest. Both Mary and John Grimké were strong advocates of the traditional, upper class Southern values that permeated Charleston society. Mary would not permit the girls to socialize outside of the prescribed elite social circles, and John proudly remained a slaveholder his entire life. Nicknamed “Nina,” young Angelina Grimké was very close to her older sister Sarah Moore Grimké, who, at age thirteen, begged her parents to allow her to be Angelina’s godmother. They consented, and the two sisters maintained a very intimate relationship throughout their lives. Even as a young child, Grimké was described in family letters and diaries as the most self-righteous, curious and self-assured of all her siblings. In the biography, The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina, historian Gerda Lerner writes that “It never occurred to [Angelina] that she should abide by the superior judgment of her male relatives or that anyone might consider her inferior, simply for being a girl.”[1] More so than her elder sister (and later, fellow abolitionist), Sarah, Grimké seemed to be naturally inquisitive and outspoken, a trait which often offended her rather traditional family and friends. When time for her confirmation in the Episcopalian Church, thirteen year old Grimké refused to recite the required pledge. Always an inquisitive and rebellious young woman, Grimké concluded that she could not agree with the pledge, and would not participate in the confirmation ceremony. Grimké promptly converted to the Presbyterian faith in April 1826. Grimké was an active member of the Presbyterian church. A proponent of biblical study and inter-faith education, she taught a Sabbath school class and also provided religious services to her family’s slaves – a practice her mother originally frowned upon, but later participated in. Grimké became a close friend of the pastor of her church, Rev. William McDowell. McDowell was a northerner who had previously been the pastor of a Presbyterian church in New Jersey. Grimké and McDowell were both very opposed to the institution of slavery on the grounds that it was a morally deficient system that violated Christian law and human rights. McDowell advocated patience and prayer over direct action against the system, which was unsatisfactory to the radical young Grimké. In 1829, she addressed the issue at a meeting in her church and stated that all slaveholding members of her congregation openly condemn the practice. Because she was such an active member of the church community, her audience respectfully declined her proposal. This incident led to Grimké’s loss of faith in the values of the Presbyterian church. With her sister Sarah’s support, Grimké adopted the tenets of the Quaker faith. The Quaker community was very small in Charleston, and Grimké quickly set out to reform her friends and family. However, given Grimké’s self-righteous nature, her comments about their wasteful and flashy behavior merely served to condescend and offend those around her. Grimké’s behavior even led to her official expulsion from the Presbyterian church in 1829. Afterwards, Grimké became convinced that the South was not the proper place for her or her work, and so she relocated to Philadelphia. After her self-induced exile from South Carolina in 1829, Grimké moved in with her sister Sarah and together they joined the Philadelphia chapter of the Religious Society of Friends. During this particular period, the Grimké sisters remained relatively ignorant of certain political issues and debates – the only periodical they read regularly was The Friend, the weekly paper of the Society of Friends. The Friend provided limited information on current events and only discussed them within the context of the Quaker community. Thus, at the time Grimké was unaware (and therefore, uninfluenced by) events such as the Webster-Hayne debates and the Maysville Veto, as well as controversial public figures such as Frances Wright. Soon after she moved to Philadelphia, Grimké’s widowed sister Anna moved in with her. Grimké was struck by the lack of options for widowed women – during this period they were mostly limited to remarriage or joining the working world – and realized the importance of education for women. She decided to become a teacher, and briefly considered attending the Female Seminary in Hartford. This institution was founded and run by Catharine Beecher, with whom Grimké would later come into public contest with. Grimké never attended the school, however, and remained in Philadelphia for the time being. Over time, Grimké became frustrated by the Quaker community’s slow and passive response to the contemporary debate on slavery. She exposed herself to more extreme abolitionist literature, such as the periodicals The Emancipator and William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator (in which she would later be published). Sarah and the traditional Quakers disapproved of Grimké’s newfound interest in radical abolitionism, but Grimké became steadily more involved in the movement. She began to attend anti-slavery meetings and lectures, and later joined the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1835. In the fall of 1835, mob violence erupted over the controversial abolitionist George Thompson. William Lloyd Garrison wrote an article in The Liberator in the hopes of calming the rioting masses. Grimké had been steadily influenced by Garrison’s work, and this article inspired her to write him a personal letter on the subject. The letter stated her concerns and opinions on the issues of abolitionism and mob violence, as well as her personal admiration for Garrison and the values he symbolized. Garrison was so impressed with Grimké’s letter that he published it in the next issue of The Liberator without her consent. Garrison also praised her for her passion, linguistic style and noble ideas. The letter put Grimké in great standing among many abolitionists, but its publication offended and stirred controversy within Quaker society, who openly condemned such radical activism. Sarah Grimké even asked her sister to withdraw the letter, concerned that such publicity would alienate her from the community. Grimké, though initially embarrassed by the letter’s publication, refused, and the letter was later reprinted in the New York Evangelist, other abolitionist papers and was also included in a pamphlet with Garrison’s noteworthy Appeal to the Citizens of Boston. In 1836, Grimké wrote her famous An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South (see below), which is often considered by scholars one of the best manifestations of Grimké’s sociopolitical agenda. Her letter to Garrison and Appeal to the Christian Women of the South gave Grimké a considerable amount of national recognition as a figure in the abolitionist movement, which enabled her to participate in many anti-slavery events, even though she was female. In 1836, she and her sister Sarah attended the Agents’ Convention of the American Anti-Slavery Society. They were the only women at the convention. There she met Theodore Dwight Weld, whom she would later marry (see Personal Life). Grimké was invited to speak at the Massachusetts State Legislature in 1837, and testified February 1838, becoming the first woman in the United States to address a legislative body. In 1838, Grimké began to tour the Northeast, giving abolitionist and feminist lectures in churches. She encouraged her older sister to speak out as well, which she did, although Grimké, a natural orator, remained the main attraction of the lectures. Abolitionist Robert F. Wolcutt stated that “Angelina Grimké’s serene, commanding eloquence enchained attention, disarmed prejudice and carried her hearers with her.”[2] Grimké’s lectures were critical of Southern slaveholders, but she also argued that Northerners tacitly complied with the status quo by purchasing slave-made products and exploiting slaves through the commercial and economic exchanges they made with slaveowners in the South. Though the Grimké sisters were strongly supported by some male abolitionists such as Weld and Garrison, they were met with a considerable amount of opposition – both because they were female and because they were abolitionists. After the lecture tour, Grimké remained a passionately active abolitionist and suffragist, until her marriage to Weld and failing health led her to lead a more domestic lifestyle. Beginning in 1831, Grimké was courted by a man named Edward Bettle, the son of Samuel and Jane Bettle, both of whom were active members of Philadelphia Quaker society. In her diary, Grimké admitted to being attracted to Bettle, but at first focused on developing her interests in the abolitionist movement and female education. Grimké’s actions were quite contrary to what was typically expected of a Quaker woman of her time – marriage. Records from Grimké’s diaries show that Bettle did intend to marry Grimké, although he never actually proposed. Sarah, Grimké’s closest family member at the time of Bettle’s courtship, supported the match. The coupling tragically did not pan out as expected. In the summer of 1832, a large cholera epidemic broke out in Philadelphia. Grimké agreed to take in Bettle’s cousin Elizabeth Walton, who, unbeknownst to anyone at the time, was dying of the disease. Bettle, who regularly visited his cousin, contracted the disease and died from it shortly thereafter. Grimké was heartbroken, and, convinced she would become a spinster, directed all of her energy into her activism.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

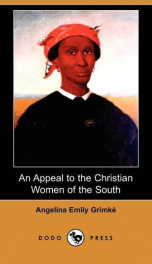

An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South (1836) was a unique piece written in the hopes that Southern women would not be able to resist an appeal made by one of their own. The style of the essay is very personal in nature, and uses simple language and firm assertions to convey her ideas. The essay is extraordinarily unique because it is the only written appeal made by a Southern woman to other Southern women regarding the abolition of slavery. Grimke's Appeal was widely distributed by the American Anti-Slavery Society, and was received with great acclaim by radical abolitionists. However, it was also received with great criticism by her former Quaker community, and was publicly burned in South Carolina. Angelina Emily Grimke Weld (1805-1879) was an American politician, lawyer, abolitionist and suffragist. Grimke was born in Charleston, South Carolina, to John Faucheraud Grimke, an aristocratic Episcopalian judge who owned slaves. She was very close to her sister Sarah Moore Grimke. In 1835, Angelina wrote an antislavery letter to Abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison, who published it in The Liberator. When her anti-slavery An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South was published in 1836, it was publicly burned in South Carolina, and she and her sister were threatened with arrest if they ever returned to their native state. At this point, Grimke and Sarah began to speak out against slavery in public. They were among the first women in the United States to break out of their designated private spheres; this made them somewhat of a curiosity. Grimke was invited to speak at the Massachusetts State Legislature in 1837, and testified February 1838, becoming the first woman in the United States to address a legislative body. In 1838, the Grimke sisters gave a series of well-attended lectures in Boston.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South (1836) was a unique piece written in the hopes that Southern women would not be able to resist an appeal made by one of their own. The style of the essay is very personal in nature, and uses simple language and firm assertions to convey her ideas. The essay is extraordinarily unique because it is the only written appeal made by a Southern woman to other Southern women regarding the abolition of slavery. Grimke's Appeal was widely distributed by the American Anti-Slavery Society, and was received with great acclaim by radical abolitionists. However, it was also received with great criticism by her former Quaker community, and was publicly burned in South Carolina. Angelina Emily Grimke Weld (1805-1879) was an American politician, lawyer, abolitionist and suffragist. Grimke was born in Charleston, South Carolina, to John Faucheraud Grimke, an aristocratic Episcopalian judge who owned slaves. She was very close to her sister Sarah Moore Grimke. In 1835, Angelina wrote an antislavery letter to Abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison, who published it in The Liberator. When her anti-slavery An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South was published in 1836, it was publicly burned in South Carolina, and she and her sister were threatened with arrest if they ever returned to their native state. At this point, Grimke and Sarah began to speak out against slavery in public. They were among the first women in the United States to break out of their designated private spheres; this made them somewhat of a curiosity. Grimke was invited to speak at the Massachusetts State Legislature in 1837, and testified February 1838, becoming the first woman in the United States to address a legislative body. In 1838, the Grimke sisters gave a series of well-attended lectures in Boston.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Grimke Angelina Emily try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Grimke Angelina Emily try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!