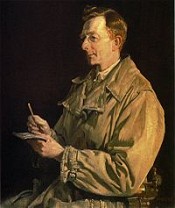

Bean Charles Edwin Woodrow

Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean (18 November 1879 – 30 August 1968), usually known during his career as C.E.W. Bean, was an Australian journalist, war correspondent and historian who is renowned as the editor of the 12-volume Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918. Bean wrote Volumes I to VI himself, dealing with the Australian Imperial Force at Gallipoli, France and Belgium. Bean was instrumental in the establishment of the Australian War Memorial, and of the creation and popularisation of the ANZAC legend. Bean was born in Bathurst, New South Wales and his family moved to England in 1889, where he was educated, firstly at Brentwood School in Essex, then from 1894 at Clifton College, Bristol, before winning a scholarship in 1898 to Hertford College, Oxford. He returned to Australia in 1904 and worked as a lawyer until June 1908 when he joined The Sydney Morning Herald as a reporter. In September 1914, Bean was selected by ballot as the official war correspondent, narrowly beating Keith Murdoch. He was given the rank of honorary captain in the AIF and followed closely in the tracks of all the Australian infantry's campaigns. Bean landed at Anzac Cove at 10am on 25 April 1915, a few hours after the first troops had landed and he remained on the peninsula for most of the campaign, enduring the same squalid conditions suffered by the soldiers. As a war correspondent, Bean's copy was detailed, accurate and also dull — he lacked the populist style of British correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett who produced the first eyewitness report from Gallipoli which was published in Australian newspapers on 8 May. As the sources for reports increased, papers such as The Age and The Argus stopped carrying Bean's copy due to its unappealing style. In early May, Bean travelled to Cape Helles with the 2nd Infantry Brigade for the Second Battle of Krithia. When the brigade was called to advance late in the afternoon on 8 May, Bean went with them from their reserve position to the starting line, under shrapnel fire the whole way. He was recommended for the Military Cross after retrieving a wounded soldier but was ineligible as his rank was only honorary. Also under fire, he carried a number of messages to the brigade commander, Brigadier General James M'Cay, close behind the front line. He made numerous trips across the battlefield, delivering water and helping to bring in the wounded, including commander of the 6th Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Walter McNicoll. On the night of 6 August,Bean was struck in the leg by a stray Turkish bullet, while following the column of Brigadier General John Monash's 4th Infantry Brigade at the start of the Battle of Sari Bair. Despite the wound, he refused to be evacuated from the peninsula. He left Gallipoli for good on the night of 17 December, two nights before the final evacuation of Anzac. He would return in 1919 with the Australian Historical Mission. When the Australian infantry moved to France in 1916, Bean followed. He continued reporting from close to the front line of all but one of the engagements involving Australian troops, and in that sense saw more action than any other Australian in the First World War. He observed first hand the "fog of war", the problems in maintaining communication between the commanders in the rear and the front line troops, and between isolated units of front line troops, and problems co-ordinating activities with other arms of the service (such as artillery) and with allied forces on each flank. He reported on the degree to which direct reports given by front line troops (and captured German soldiers) could be misleading given their limited view of the battlefield and the effect of the shock of fierce fighting and devastating artillery fire. It was during this period that Bean began planning for the post-war preservation of the Anzac legacy via the establishment of a permanent museum and memorial, and by the collection of records relating to Australia's war effort. On 16 May 1917 the Australian War Records Section was established under the command of Captain John Treloar to manage the collection of documents and relics. Attached to the section were members of the Australian Salvage Corps who would select items of interest from the battlefield detritus they recovered for scrap or repair. Treloar was subsequently appointed the first director of the Australian War Memorial in 1920. He had a 15 pound clothing allowance and spent this on making what would become his 'distinctive outfit.' He was also equipped with a horse and saddlery. Private Arthur Bazley was assigned as Bean's batman, and the two soon became friends. Bean's influence grew as the war progressed and he lobbied (along with Keith Murdoch, father of Rupert Murdoch) unsuccessfully against the appointment of General John Monash to the command of the Australian Corps in 1918. He disliked Monash for not fitting his ideal of Australian manhood (Monash was of Jewish background) and his promotion of his men — he had earned Monash's wrath for failing to publicise his brigade at Anzac — which Bean viewed as a penchant for self-promotion and wrote in his diary, "We do not want Australia represented by men mainly because of their ability, natural and inborn in Jews, to push themselves." (embarrassingly anti-semitic today, it was a common prejudice at the time) Bean favoured the appointment of the Australian Chief of General Staff, Brudenell White, the meticulous planner behind the successful withdrawal from Gallipoli, or General Birdwood, the British commander of the Australian forces at Gallipoli. Despite his opposition to the appointment of Monash, Bean later acknowledged Monash's success in the role, noting that he had made a better Corps commander than a Brigade commander (and as an aside admitting that his role in trying to influence the decision had been improper). Bean's brother was an anaesthetist and served as a major in the Medical Corps on the Western Front. In 1916 the British War Cabinet had agreed to grant Dominion official historians access to the war diaries of all British Army units fighting on either side of a Dominion unit, as well as all headquarters that issued orders to Dominion units, including the GHQ of the British Expeditionary Force. By the end of the war, the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) were less than willing to divulge this information, possibly fearing it would be used to criticise the conduct of the war. It took six years of persistence before Bean was allowed access and a further three years for a clerk to make copies of the enormous quantity of documents. Bean therefore had available to him resources that were denied to all British historians who were not associated with the Historical Section of the CID. Bean was unwilling to compromise his values for personal gain or political expediency. He was not influenced by suggestions and criticism from British official historian, Sir James Edmonds about the direction of his work. Edmonds reported to the CID that, "The general tone of Bean's narrative is deplorable from the Imperial standpoint." For his maverick stance, it is likely that Bean was denied decorations from King George V, despite being recommended on two occasions during the war by the commander of the Australian Corps. Bean was not motivated by personal glory; many years later when he was offered a knighthood, he declined.[1] In 1919 Bean led the Australian Historical Mission back to the Gallipoli peninsula to revisit the battlefield of 1915. For the first time he was able to walk over ground where some of the famous battles were fought such as Lone Pine and at the Nek, where he found the bones of the light horsemen still lying where they fell on the morning of 7 August 1915. He also instructed the Australian Flying Corps, one of the few Australian units involved in the occupation forces in Germany, to collect German aircraft to be returned to Australia; they obtained a Pfalz D.XII and an Albatros D.Va. Upon his return to Australia in 1919, Bean commenced work with a team of researchers on the Official History and the first volume, covering the formation of the AIF and the landing at Anzac Cove, was published in 1921. It would be 21 years before the last of the 12 volumes (Volume VI) was published. Bean personally wrote the first 6 volumes covering the Army involvement. In 1946 he published Anzac to Amiens, a condensed version of the Official History — this was the only book to which he owned the copyright and received royalties. Bean's style of War History was different to anything that had gone before. Partly reflecting his background as a journalist, he concentrated on both the 'little people' and the big themes of the First World War. The smaller size of the Australian Army contingent (240,000) allowed him to describe the action in many cases down to the level of individuals, which suited Bean's theme that the achievement of the Australian Army was the story of those individuals as much as it was of Generals or politicians. Bean was also fascinated by the Australian character, and used the history to describe, and in some way create, a somewhat idealised view of an Australian character that looked back at its British origins but had also broken free from the limitations of that society. Bean's approach, despite his prejudices and his intention to make the history a statement about society, was to meticulously record and analyse what had happened on the battlefields. His method was generally to describe the wider theatre of war, and then the detailed planning behind each battle. He then moved to the Australian commander's perspectives and contrasted these with the impressions from the troops at the front line (usually gathered by Bean 'on the spot'). He then went further and quoted extensively from the German (or Turkish) records of the same engagement, and finally summarised what had actually happened (often using forensic techniques going over the ground after the war). All throughout he noted the individual Australian casualties where there was any evidence of the circumstances of their death. Even with that small contingent of 240,000 (of whom 60,000 died) this was a monumental task, particularly as the Australians had been used, much as the Canadians, as shock troops by the British command wherever the line was most threatened, or where there was need to mount an attack. Bean also — uniquely — reported ultimately on his own involvement in the maneuvering around command decisions regarding Gallipoli, and the appointment of the Australian Corps Commander, and did not spare himself some criticism with the wisdom of hindsight.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Letters from France

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: CHAPTER III THE FIRST IMPRESSIONA COUNTRY WITH EYES France, April, 1916. Rich green meadows. Rows of tall, slender elm trees along the hedges. Low, stunted and pollarded willows lining some distant ditch, with their thick trunks showing notched against a distant blue hill-side like a row of soldiers. Here and there a red roof nestled among the hawthorn under the tall trees just bursting into green. Violetsgreat bunches of them in the patches of scrub between the tall trunks and yellow cowslips and white and pink anemones and primroses. You see the flaxen- haired children out in the woods and along the roadside gathering them. A rosy-cheeked woman stands in the doorway of a farm at the cross-roads, and a golden-haired youngster, scarce able to run as yet, totters across the road to her, laughing. Only this morning, as we passed that samehouse, there was the low whine of a shell, and a metallic bang like the sound of a dented kerosene tin when you try to straighten the bend in it. Then another and another and another. We could see the white smoke of the shells floating past behind the spring greenery of a hedgerow only a few fields away. It drifted slowly through the trees and then came another salvo. There were some red roofs nearthose of a neighbouring farmbut we could not see whether they were firing at them, or at some sign of moving troops, or at a working party if there were any; and I do not know now. As we came back that way in the afternoon there was more shelling farther along. The woman in the doorway simply turned her head in its direction for a moment, and so did a younger woman who came to the doorway behind her. Then they turned to the baby again. Through the trees one could see that the farmhouses and cottages farther on had mostly been battered and ... --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Letters from France

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: CHAPTER III THE FIRST IMPRESSIONA COUNTRY WITH EYES France, April, 1916. Rich green meadows. Rows of tall, slender elm trees along the hedges. Low, stunted and pollarded willows lining some distant ditch, with their thick trunks showing notched against a distant blue hill-side like a row of soldiers. Here and there a red roof nestled among the hawthorn under the tall trees just bursting into green. Violetsgreat bunches of them in the patches of scrub between the tall trunks and yellow cowslips and white and pink anemones and primroses. You see the flaxen- haired children out in the woods and along the roadside gathering them. A rosy-cheeked woman stands in the doorway of a farm at the cross-roads, and a golden-haired youngster, scarce able to run as yet, totters across the road to her, laughing. Only this morning, as we passed that samehouse, there was the low whine of a shell, and a metallic bang like the sound of a dented kerosene tin when you try to straighten the bend in it. Then another and another and another. We could see the white smoke of the shells floating past behind the spring greenery of a hedgerow only a few fields away. It drifted slowly through the trees and then came another salvo. There were some red roofs nearthose of a neighbouring farmbut we could not see whether they were firing at them, or at some sign of moving troops, or at a working party if there were any; and I do not know now. As we came back that way in the afternoon there was more shelling farther along. The woman in the doorway simply turned her head in its direction for a moment, and so did a younger woman who came to the doorway behind her. Then they turned to the baby again. Through the trees one could see that the farmhouses and cottages farther on had mostly been battered and ... --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Bean Charles Edwin Woodrow try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Bean Charles Edwin Woodrow try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!