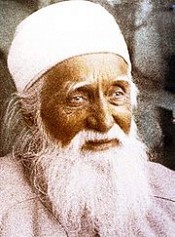

`Abdu'l-Bahá

‘Abdu’l-Bahá (عبد البهاء) (23 May 1844 - 28 November 1921), born `Abbás Effendí, was the eldest son of Bahá'u'lláh,[1] the founder of the Bahá'í Faith. In 1892, `Abdu'l-Bahá was appointed in his father's will to be his successor and head of the Bahá'í Faith.[2][3] His journeys to the West, and his Tablets of the Divine Plan spread the Bahá'í message beyond its middle-eastern roots, and his Will and Testament laid the foundation for the current Bahá'í administrative order. `Abdu'l-Bahá's given name was `Abbás, but he preferred the title of `Abdu'l-Bahá (servant of the glory of God). He is commonly referred to in Bahá'í texts as "The Master", and received the title of KBE after his personal storage of grain was used to relieve famine in Palestine following World War I, but never used the title. `Abdu'l-Bahá was born in Tehran, Iran on 23 May 1844 (5th of Jamadiyu'l-Avval, 1260 AH),[4] the eldest son of Bahá'u'lláh and Navváb. He was born on the very same night on which the Báb declared his mission.[5] During his youth, `Abdu'l-Bahá was shaped by his father's station as a prominent member of the Bábís.`Abdu’l-Bahá spent his early years in an environment of privilege, wealth, and love. The family’s Tehran home and country houses were comfortable and beautifully decorated. `Abdu’l-Bahá and his younger siblings— a sister, Bahíyyih, and a brother, Mihdí— had every advantage their station in life could offer.[6] One event that affected `Abdu'l-Bahá greatly during his childhood was the imprisonment of his father when `Abdu'l-Bahá was eight years old; the imprisonment led to his family being reduced to poverty and being attacked in the streets by other children. Esslemont records that "A mob sacked their house, and the family were stripped of their possessions and left in destitution."[5] Bahá'u'lláh was eventually released from prison but ordered into exile, and `Abdu'l-Bahá joined his father on the journey to Baghdad in the winter of 1853.[7] During the journey `Abdu'l-Bahá suffered from frost-bite. When Bahá'u'lláh secretly secluded himself in the mountains of Sulaymaniyah in 1854, `Abdu'l-Bahá was no more than ten years old and grieved over his separation from his father.[8] During his years in Baghdad, `Abdu'l-Bahá spent much of his time reading the writings of the Báb, wrote commentary on Qur'anic verses and conversed with the learned of the city.[8] In 1856, when news of a personage in the mountains of Kurdistan arrived, `Abdu'l-Baha along with some family and friends set out to ask Bahá'u'lláh to return to Baghdad.[9] In 1863 Bahá'u'lláh was summoned to Constantinople (Istanbul), and thus his whole family including `Abdu'l-Bahá, then nineteen, accompanied him on his 110-day journey.[10] `Abdu'l-Baha followed his father through the further exile to Adrianople (Edirne), and finally Akká, Palestine (now Acre, Israel). During this time he increasingly assumed the role of Bahá'u'lláh's chief steward.[11] On arrival in Akka, due to the unsanitary state of its barracks, many of the Bahá'ís fell sick, and `Abdu'l-Bahá tended the sick. Furthermore, the inhabitants of Akka were told that the new prisoners were enemies of the state, of God and his religion, and that association with them was strictly forbidden, and thus the Bahá'ís were faced with hostile officials, and scornful inhabitants and `Abdu'l-Bahá shielded his father of much of these attacks.[12] Over time, he gradually took over responsibility for the relationships between the small Bahá'i exile community and the outside world. It was through his interaction with the people of Akka that, according to the Bahá'ís, they recognized the innocence of the Bahá'ís, and thus the conditions of imprisonment were eased. Eventually, Bahá'u'lláh was allowed to leave the city and visit nearby places.[13] As a young man speculation was rife amongst the Bahá’ís to whom `Abdu’l-Bahá would marry.[5] Several young girls were seen as marriage prospects but `Abdu’l-Bahá seemed disinclined to marriage.[5] On March 8 1873, at the urging of his father,[14] the twenty-eight-year-old `Abdu’l-Bahá married Fátimih Nahrí of Isfahán (1847-1938) a twenty-five-year-old noblewoman.[15] Her father was Mírzá Muḥammad `Alí Nahrí of Isfahan an eminent Bahá’í of the city and prominent aristocrat.[5] Fátimih was bought from Persia to Acre, Israel after both Bahá’u’lláh and his wife Navváb expressed an interest in her to marry `Abdu’l-Bahá.[5][15][16] After a wearisome journey from Isfahán to Akka she finally arrived accompanied by her brother in 1872.[5][16] The marriage resulted in nine children: two boys: Ḥusayn Effendi (d. 1305/1887, aged five) and Mihdí (died aged two-and-a-half) and seven daughters: Ṭúbá (died sometime in Akka), Fu'ádíyyih (died in infancy), and Ruḥangíz (died in 1893, she was the favorite grandchild of Bahá'u'lláh).[17] Four children survived adulthood all daughters; Ḍiyá'iyyih Khánum (mother of Shoghi Effendi) (d. 1951) Túbá Khánum (1880-1959) Rúḥá Khánum and Munavvar Khánum (d. 1971).[5] Bahá'u'lláh wished that the Bahá'ís follow the example of `Abdu'l-Bahá and gradually move away from polygamy.[16][18] The marriage of `Abdu’l-Bahá to one woman and his choice to remain monogamous[16], from advice of his father and his own wish,[16][18] legitimised the practice of monogamy[18] to a people whom hitherto had regarded polygamy and a righteous way of life.[16][18] After Bahá'u'lláh died on 29 May 1892, the Will and Testament of Bahá'u'lláh named `Abdu'l-Bahá as Centre of the Covenant, successor and interpreter of Bahá'u'lláh's writings.[2] In the Will and Testament `Abdu'l-Bahá's half-brother, Muhammad `Alí, was mentioned by name as being subordinate to `Abdu'l-Bahá. Muhammad `Alí became jealous of his half-brother and set out to establish authority for himself as an alternative leader with the support of his brothers Badi'u'llah and Diya'u'llah.[4] He began correspondence with Bahá'ís in Iran, initially in secret, casting doubts in others' minds about `Abdu'l-Bahá.[19] While most Bahá'ís followed `Abdu'l-Bahá, a handful followed Muhammad `Alí including such leaders as Mirza Javad and Ibrahim Khayru'llah, the famous Bahá'í missionary to America.[20] Muhammad `Alí and Mirza Javad began to openly accuse `Abdu'l-Bahá of taking on too much authority, suggesting that he believed himself to be a Manifestation of God, equal in status to Bahá'u'lláh.[21] It was at this time that `Abdu'l-Bahá, in order to provide proof of the falsity of the accusations levelled against him, in tablets to the West, stated that he was to be known as "`Abdu'l-Bahá" an Arabic phrase meaning the Servant of Bahá to make it clear that he was not a Manifestation of God, and that his station was only servitude.[22] It was as a result of this breakdown in relations between the half-brothers that when `Abdu'l-Bahá died, instead of appointing Muhammad `Alí, he left a Will and Testament that set up the framework of an administration. The two highest institutions were the Universal House of Justice, and the Guardianship, for which he appointed Shoghi Effendi as the Guardian.[2] By the end of 1898, Western pilgrims started coming to Akka on pilgrimage to visit `Abdu'l-Bahá; this group of pilgrims, including Phoebe Hearst, was the first time that Bahá'ís raised up in the West had met `Abdu'l-Bahá.[23] During the next decade `Abdu'l-Bahá would be in constant communication with Bahá'ís around the world, helping them to teach the religion; the group included May Ellis Bolles in Paris, Englishman Thomas Breakwell, American Herbert Hopper, French Hippolyte Dreyfus, Susan Moody, Lua Getsinger, and American Laura Clifford Barney.[24] It was Laura Clifford Barney who, by asking questions of `Abdu'l-Bahá over many years and many visits to Haifa, compiled what later became the book Some Answered Questions.[25] During the final years of the 19th century, while `Abdu'l-Bahá was still officially a prisoner and confined to `Akka, he organized the transfer of the remains of the Báb from Iran to Palestine. He then organized the purchase of land on Mount Carmel that Bahá'u'lláh had instructed should be used to lay the remains of the Báb, and organized for the construction of the Shrine of the Báb. This process took another 10 years.[26] With the increase of pilgrims visiting `Abdu'l-Bahá, Muhammad `Alí worked with the Ottoman authorities to re-introduce stricter terms on `Abdu'l-Bahá's imprisonment in August 1901.[2][27] By 1902, however, due to the Governor of `Akka being supportive of `Abdu'l-Bahá, the situation was greatly eased; while pilgrims were able to once again visit `Abdu'l-Bahá, he was confined to the city.[27] In February 1903, two followers of Muhammad `Alí, including Badi'u'llah and Siyyid `Aliy-i-Afnan, broke with Muhammad `Ali and wrote books and letters giving details of Muhammad `Ali's plots and noting that what was circulating about `Abdu'l-Bahá was fabrication.[28][29] From 1902-1904, in addition to the building of the Shrine of the Báb that `Abdu'l-Bahá was directing, he started to put into execution two different projects; the restoration of the House of the Báb in Shiraz, Iran and the construction of the first Bahá'í House of Worship in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan.[30] `Abdu'l-Bahá asked Aqa Mirza Aqa to coordinate the work so that the house of the Báb would be restored to the state that it was at the time of the Báb's declaration to Mulla Husayn in 1844;[30] he also entrusted the work on the House of Worship to Vakil-u'd-Dawlih.[31] Also in 1904, Muhammad `Ali continued his accusations against `Abdu'l-Bahá which caused an Ottoman commission summoning `Abdu'l-Bahá to answer the accusations levelled against him. During the inquiry the charges against him were dropped and the inquiry collapsed.[32][33] The next few years in `Akka were relatively free of pressures and pilgrims were able to come and visit `Abdu'l-Bahá. Also, by 1909 the mausoleum of the shrine of the Báb was completed.[31] The 1908 Young Turks revolution freed all political prisoners in the Ottoman Empire, and `Abdu'l-Bahá was freed from imprisonment. His first action after his freedom was to visit the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh in Bahji.[34] While `Abdu'l-Bahá continued to live in `Akka immediately following the revolution, he soon moved to live in Haifa near the Shrine of the Báb.[34] In 1910, with the freedom to leave the country, he embarked on a three year journey to Egypt, Europe, and North America, spreading the Bahá'í message.[2]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Bahá’í Prayers: A Selection of Prayers Revealed by Bahá’u’lláh, the

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Bahá’í Prayers: A Selection of Prayers Revealed by Bahá’u’lláh, the

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like `Abdu'l-Bahá try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like `Abdu'l-Bahá try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!