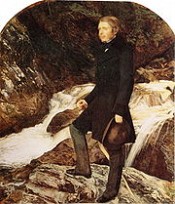

Ruskin John

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 – 20 January 1900) was an English art critic and social thinker, also remembered as an author, poet and artist. His essays on art and architecture were extremely influential in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Ruskin first came to widespread attention for his support for the work of J. M. W. Turner and his defence of naturalism in art. He subsequently put his weight behind the Pre-Raphaelite movement. His later writings became increasingly complex and personal explorations of the interconnection of cultural social and moral issues and were influential on the development of Christian socialism. His voluminous output and authoritative tone led Ruskin to epitomise the Victorian sage. Ruskin was born in London and raised in South London, the only child of a wine importer who co-founded the company that became Allied Domecq. He was educated at home and went on to study at King's College London and Christ Church, Oxford. At Oxford, he enrolled as a "gentleman-commoner", a class of students who were not expected to pursue a full course of study. His own studies were erratic, and he was often absent. However, he impressed the scholars of Christ Church after he won the Newdigate prize for poetry, his earliest interest. In consequence and despite a protracted period of serious illness, Oxford awarded him an honorary fourth-class degree. Ruskin's first published prose work came in 1834 when, at age 15, he began writing a series of articles for Loudon's Magazine of Natural History. In 1836-37, he wrote The Poetry of Architecture, serialised in Loudon's Architectural Magazine, under the pen name "Kata Phusin" (Greek for "according to Nature"). This was a study of cottages, villas, and other dwellings which centered around a Wordsworthian argument that buildings should be sympathetic to local environments, and should use local materials. Soon afterward, in 1839, he published, in Transactions of the Meteorological Society (pages 56–59), his "Remarks on the present state of meteorological science". He went on to publish the first volume of one of his major works, Modern Painters, in 1843, under the anonymous identity "An Oxford Graduate". This work argued that modern landscape painters — and in particular J. M. W. Turner— were superior to the so-called "Old Masters" of the post-Renaissance period. Such a claim was controversial, especially as Turner's semi-abstract late works were being denounced by some critics as meaningless daubs. The degree to which Ruskin reversed an anti-Turnerian tide may have been overemphasised in the past, as Turner was a renowned and major figure in the early Victorian art world and a prominent member of the Royal Academy. Ruskin's criticism of Old Masters like Gaspard Dughet (Gaspar Poussin), Claude Lorrain, and Salvator Rosa, was much more controversial, given the immense respect they held at the time. The attack on the old masters centred on what Ruskin perceived as their lack of attention to natural truth. Rather than 'going to nature', as Turner did, the old masters, 'composed' or invented their landscapes in their studios. For Ruskin, modern painters like Turner and James Duffield Harding (Ruskin's art tutor) showed a much more profound understanding of nature, observing the 'truths' of water, air, clouds, stones, and vegetation. Ruskin considered some Renaissance masters, notably Titian and Dürer, to have shown similar devotion to nature, but he attacked even Michelangelo as a corrupting influence on art. The second half of Modern Painters I consists of detailed observations by Ruskin of exactly how clouds move, how seas appear at different times of day, or how trees grow, followed by examples of error or truth from various artists. Ruskin had already met and befriended Turner, and eventually became one of the executors of his will. Many long believed that, as an executor, Ruskin took it upon himself in 1858 to destroy a large number of Turner's sketches because of their 'pornographic' subject matter but more recent discoveries cast doubt on this idea (see below). Ruskin followed Modern Painters I with a second volume, developing his ideas about symbolism in art. He then turned to architecture, writing The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice, both of which argued that architecture cannot be separated from morality, and that the "Decorated Gothic" style was the highest form of architecture yet achieved.[2] By this time, Ruskin was writing in his own name and had become the most famous cultural theorist of his day. In 1848, he married Effie Gray, for whom he wrote the early fantasy novel The King of the Golden River. Their marriage was notoriously unhappy, eventually being annulled in 1854 on grounds of his "incurable impotency,"[3] a charge Ruskin later disputed, even going so far as to offer to prove his virility at the court's request[4]. In court, the Ruskin family counter-attacked Effie as being mentally unbalanced. Effie later married the artist John Everett Millais, who had been Ruskin's protegé, in July 1855. Ruskin came into contact with Millais following the controversy over Millais's painting Christ in the House of His Parents, which was considered blasphemous at the time. Millais, with his colleagues William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, had established the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. The Pre-Raphaelites were influenced by Ruskin's theories. As a result, the critic wrote letters to The Times defending their work, later meeting them. Initially, he favoured Millais, who travelled to Scotland with Ruskin and Effie to paint Ruskin's portrait. Effie's increasing attachment to Millais, among other reasons (including Ruskin's non-Consummation of the marriage[5]) created a crisis, leading Effie to leave Ruskin, which caused a public scandal. Millais abandoned the Pre-Raphaelite style after his marriage, and Ruskin often savagely attacked his later works. Ruskin continued to support Hunt and Rossetti. He also provided independent funds to encourage the art of Rossetti's wife Elizabeth Siddal. Other artists influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites also received both written and financial support from him, including John Brett, Burne-Jones. and John William Inchbold. In 1858 he also opened the School of Art in Sidney Street, Cambridge, laying the foundation for what is now Anglia Ruskin University. During this period Ruskin wrote regular reviews of the annual exhibitions at the Royal Academy under the title Academy Notes. His reviews were so influential and so judgmental that he alienated many artists, leading to much comment. For example, Punch published a comic poem about a victim of the critic, which contained the lines, "I paints and paints, hears no complaints...then savage Ruskin sticks his tusk in and nobody will buy." Ruskin also sought to encourage new architecture based on his theories. He was friendly with Sir Henry Acland, who supported his attempts to get the new Oxford University Museum of Natural History built as a model of modern Gothic. Ruskin also inspired other architects to adapt the Gothic style for modern culture. These buildings created what has been called a distinctive "Ruskinian Gothic" style.[6] Following a crisis of religious belief, and under the influence of his great friend Thomas Carlyle, Ruskin abandoned art criticism at the end of the 1850s, moving towards commentary on politics. In Unto This Last, he expounded theories about social justice, which influenced the development of the British Labour party and Christian socialism. On his father's death, Ruskin declared it was not possible to be a rich socialist, and gave away most of his inheritance. He founded the charity known as the Guild of St George in the 1870s, and endowed it with large sums of money and a remarkable art collection. He gave money to enable Octavia Hill to begin her practical campaign of housing reform. He attempted to reach a wide readership with his pamphlets Fors Clavigera, aimed at the "working men of England". He taught at the Working Men's College, London, and was the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford, from 1869 to 1879. His lectures were so popular that they had to be given twice — once for the students, and again for the public. Ruskin College, Oxford is named after him. While at Oxford, Ruskin became friendly with Lewis Carroll, another don, who photographed him. After Carroll parted with Alice Liddell, she and her sisters pursued a similar relationship with Ruskin, according to his autobiography, Praeterita. During this period Ruskin became enamoured of Rose la Touche, an intensely religious girl, whom he met through his patronage of Louisa, Marchioness of Waterford, a talented watercolourist. He was introduced to Rose in 1858, when she was only ten years old, proposed to her eight years later, and was finally rejected in 1872. She died soon afterward. These events plunged Ruskin into despair and led to bouts of mental illness. He suffered from a number of breakdowns and delirious visions. In 1878, he published a scathing review of paintings by James McNeill Whistler exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery. He found particular fault with Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, and accused Whistler of "ask[ing] two hundred guineas for throwing a pot of paint in the public's face." [7] Whistler filed a libel suit against Ruskin. Whistler won the case, but the jury awarded him only one farthing for damages; it split court costs between Ruskin and Whistler. The episode tarnished Ruskin's reputation, and may have accelerated his mental decline. The emergence of the Aesthetic movement and Impressionism alienated Ruskin from the art world, and his later writings were increasingly seen as irrelevant, especially as he seemed to be more interested in book illustrators such as Kate Greenaway than in modern art. He continued to support philanthropic movements such as the Home Arts and Industries Association Much of his later life was spent at a house called Brantwood, on the shores of Coniston Water located in the Lake District of England. His assistant W. G. Collingwood, the author, artist and antiquarian lived nearby and in 1901 established the Ruskin Museum in Coniston as a memorial to Ruskin.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Letters to the ClergyOn The Lord's Prayer and the Church

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Modern Painters. Vol. III (of V)Containing Part IV. Of Many Things

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Unto This Last and Other Essays on Political Economy

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Letters to the ClergyOn The Lord's Prayer and the Church

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Modern Painters. Vol. III (of V)Containing Part IV. Of Many Things

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Unto This Last and Other Essays on Political Economy

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The King of the Golden River or the Black BrothersA Legend of Stiria.

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Time and Tide by Weare and TyneTwenty-five Letters to a Working Man of Sunderland on the Laws of Work

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Frondes AgrestesReadings in 'Modern Painters'

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Elements of DrawingIn Three Letters to Beginners

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Saint UrsulaStory of Ursula and Dream of Ursula

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Ariadne FlorentinaSix Lectures on Wood and Metal Engraving

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Crown of Wild Olivealso Munera Pulveris; Pre-Raphaelitism; Aratra Pentelici; The Ethics of the Dust; Fiction,Fair and Foul; The Elements of Drawing

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Aratra Pentelici,Seven Lectures on the Elements of SculptureGiven before the University of Oxford in Michaelmas Term,1870

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

On the Old Road Vol. 1 (of 2)A Collection of Miscellaneous Essays and Articles on Art and Literature

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Ruskin John try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Ruskin John try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!